Lasagna,Layers and Timelines: Making Sense of History.

- vmramshur

- Oct 29, 2024

- 6 min read

Back from my travels, Before I write more blog posts, research articles, or begin any creative projects, I need to sift through the layers of history with fresh eyes—I am ready to untangle the threads and weave ideas into new art and design projects, and my course work and syllabi.

Teaching a design-based history course can feel like an endless puzzle. In my courses, “History of Costume and Décor” and “Costume History Seminar”, I’ve tasked myself with guiding students from antiquity to the 21st century. The challenge? The class isn’t “big” because of the number of students—it’s big in scope. Too big. Every year, I rewrite, experiment with new approaches, and fret over what’s left in and what’s left out. It's never the same course twice, and while I love it, I know it can be overwhelming for my students. I bombard them with content, finding it all too fascinating to trim down. But after countless workshops, seminars, and peer-led classes I know I'm not alone in wanting my course to be as inclusive, dynamic, and engaging as possible.

In teaching, I’ve often compared history to a lasagna—layers of interconnected events. It’s hardly a groundbreaking idea, but it does help students see that history is not a string of isolated moments but a continuum. Yet, as a designer, I’ve come to realize that a lasagna metaphor doesn’t quite fit. So, I’ve decided to swap the lasagna for something closer to my field: fabric. History is like layers of fabric stitched together over time, creating a rich, textured tapestry of interwoven events and cultures.

Back to “The Lasagna Layers” of History… indulge me.

Let’s start with the lasagna metaphor—it’s a bit quirky but helps make sense of history’s complexity. Just as a lasagna has distinct layers, each adding flavor and depth, so does history. Our world is shaped by accumulating events, traditions, and cultures that influence each other across time. History isn’t just one thing at a time; it’s a deliciously messy stack of moments interacting across centuries.

This concept isn’t new, of course. Take Fernand Braudel from the Annales School,

Braudel , who developed the idea of “la longue durée” (the long term) argued that history isn’t shaped only by headline events like wars or revolutions but by the slow forces of geography, climate, and social structures. Think of these as the deeper layers in the lasagna. Events like battles are the surface cheese layer, but the meat of history lies in the social and environmental forces simmering below.

And archaeologists? They’ve been unearthing historical layers for decades. For them, history is revealed in strata, each representing a different period. Digging through these layers is like peeling back lasagna to uncover different flavors—a messy but rewarding process that gives us richer insights into human life over time.

OK …NOW Shifting to Fabric: History as a Tapestry

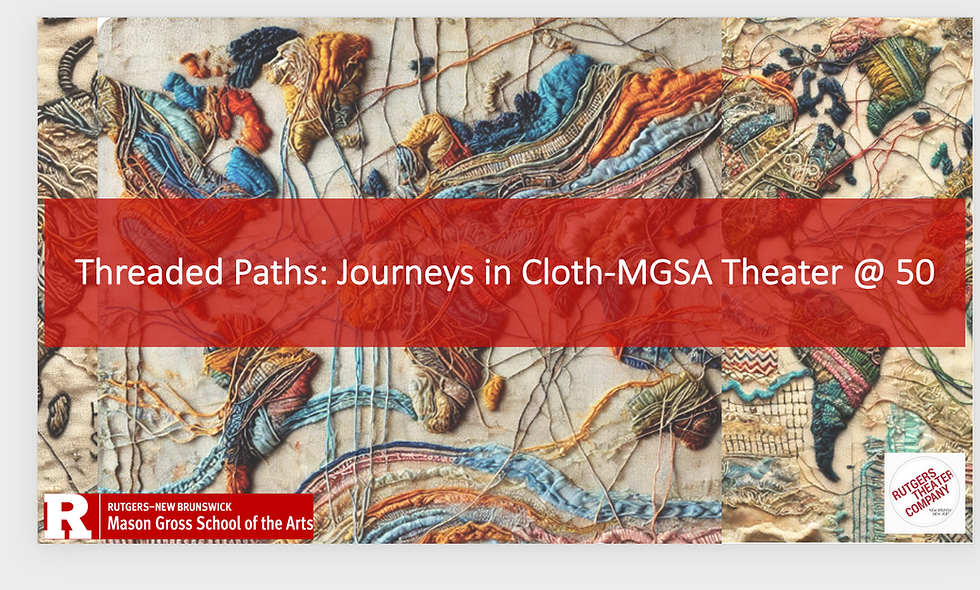

But lasagna aside, fabric feels like a more fitting metaphor for design students. Imagine history as layers of fabric, each representing an era, stitched together into a garment that’s still evolving. Just as a beautifully crafted garment has layers that add structure, texture and depth, history is a woven masterpiece, with each thread intertwined across centuries.

Braudel’s ideas on la longue durée fit well here, too. He saw the true fabric of history not in surface-level events but in the deep, long-term forces shaping civilization. Think of these forces as the foundational fabrics, while individual events are the decorative embroidery on top. The true “design” of history lies not in the surface patterns but in the deeper weave that supports it all.

Archaeologists, in this sense, are like expert tailors, and costume technicians, unpicking seams to reveal the past. Every layer of fabric represents a distinct period of human activity. Unearthing these layers is like discovering a different textile, revealing clues about life in that era. Earlier periods aren’t erased but repurposed, just waiting beneath the surface, like the hidden stitches in a garment.

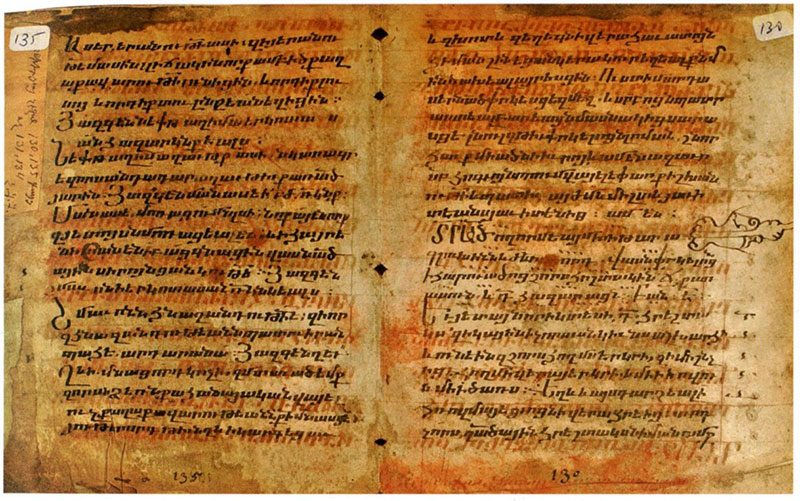

The Palimpsest: Hidden Threads of the Past

Historians often use the term “palimpsest” to describe this layered nature of history. Traditionally, a palimpsest is a manuscript—typically of papyrus or parchment—that has been written on more than once, with earlier writing partially scraped off or erased yet still faintly visible beneath the surface. These traces of old writing can still be legible, hinting at stories and knowledge that endure despite being “overwritten.”

In a broader sense, a palimpsest can refer to any object or area with layers showing extensive evidence of activity or use. New events and cultures might “overwrite” the old, but the original imprints remain, barely visible yet undeniably present. History, like a reworked manuscript, is constantly rewritten, yet it never fully erases what came before. Just as the earlier text of a palimpsest still shows through, we can see the layers of history even when new events seem to dominate, much like the original threads showing through a new design.

Cultural Historians and the Garment of Time

Cultural historians often speak of culture as a series of layered garments, with each era's customs and practices stitched into newer fabrics. A centuries-old tradition can be like an ancient textile, finding new life in modern clothing—where the old and the new coexist, influencing one another. This isn’t just about preserving relics from the past; it’s about how history and culture are woven into our daily lives, shaping our actions, beliefs, and aesthetics. The metaphor reveals how the past isn't static but instead actively threads its way through everything we do today, in both obvious and nuanced ways.

Key Thinkers: 20thc Designers ( not fashion) of History's Layers

Here’s a quick look at some historical “designers” who shaped our layered view of the past:

Fernand Braudel: The master tailor of la longue durée, who showed how long-term forces weave through the fabric of history.

Jacques Le Goff: Another Annales historian, who studied medieval societies by examining layers of time, religion, and economy.

Michel Foucault: A philosopher who saw history as a patchwork of discursive layers, with each era spinning its own “fabric of truth.”

Carlo Ginzburg: A microhistorian who zoomed in on small details to reveal sweeping social and cultural patterns.

David Christian: Known for Big History, linking the Big Bang to today into one vast fabric of time and space.

Why Historical Timelines Are So Damn Fun (and Why We Shouldn’t Trust Them Completely)

There’s something magnetic about a good historical timeline. Watching a whole story unfold across one tidy line makes history feel manageable, like we’re “walking through time.” Timelines simplify vast amounts of information into clean, visual nuggets, creating a sense of accessibility. But here’s the kicker: timelines often hide major academic blind spots. Many historical records are fragmented, and the timelines we see often reflect the voices that survived, not the full story.

Timelines are visually appealing and reveal fascinating connections across cultures. They suggest patterns but can also mislead, creating a sense of causation where none exists. They’re at best frameworks, not certainties. And they’re heavily biased—constructed from the perspectives of those who historically held power, which often skews them toward the dominant narratives.

So while timelines create a sense of structure and connection, they’re ultimately invitations to inquiry, not finish lines of certainty. They’re a lively conversation with history, a chance to enjoy the connections and patterns they suggest while recognizing there’s always more behind the line than meets the eye.

Wrapping It Up

Whether we see history as layers of lasagna or a multi-layered fabric, the message is the same: history is not a series of isolated events. It’s a continuum, where every culture, tradition, and event builds upon what came before, creating an interwoven tapestry of time. So the next time someone brings up historical theories at a gathering, you can confidently talk about history as layers—whether it’s a fabric or a lasagna.

If you're interested, take a look at this site—it’s full of fun visual timelines, I warn you, it is a rabbit hole.

How do you like your history? Layered like a well-crafted garment or reworked like a palimpsest? Let’s keep the conversation going!

-Val

Terrific and thought provoking!

I am being particularly drawn to this idea of time and history being woven like a fine fabric. Maybe it is my brain, as a lover of science and textiles, but wow, something really clicked for me reading your perspective on this Val. I cant help but feel like this conversation could be "unraveled" (haha) further to talk about when fabric not only figuratively a way to look a history, but also a literal one. Heraldic embroidery or, dare I say, tabbards come to mind ! Another great read. Thank you!!

so well written and so fascinating